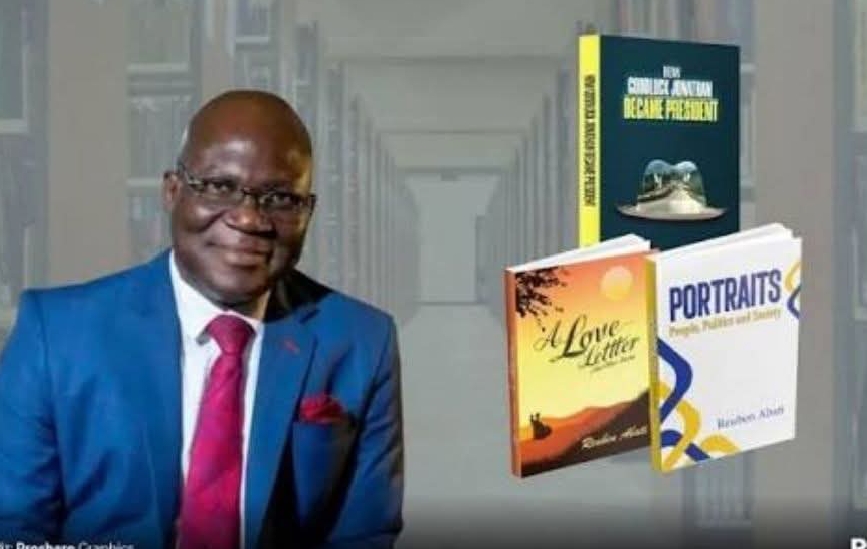

The Essayist as Bearer of National Memory: A Review of Reuben Abati’s 3-Part Offering

Abati and His Books

By Louis Odion, FNGE

Among top Nigerian editors of the last three decades, the mention of the word “monumental” only signifies one individual — Dr Reuben Abati. It has nothing to do with the topography or archaeology of his native Egbaland; but rather it’s an acknowledgement by media contemporaries of Abati’s prodigious capacity for both hard-work and play; that capacity to engage in scholarly circuits as well as tease flawlessly in street lingo; the facility to deliver a brilliant lecture at short notice and yet never failing to meet editorial deadlines to his primary employer.

To multi-task as a writer, bibliophile, TV/Radio anchor, speaker, dramatist, compere, wine connoisseur and — I must not forget to add — a very good lover of beautiful women. And yet, never disappointing in each task or role. If you like, call him a Jack of all trades, but he is a master of all.

That is why you would hear the shout of “monumental! monumental !!” when Dr. Abati joins the gathering of his media associates. Only that could explain why Abati who, for instance, was heard giving an impeccable summary of the presentation by a visiting high-profile guest at The Niteshift Coliseum nightclub by Sunday midnight as the in-house moderator, would yet be among the first to be seated at the the editorial board meeting of The Guardian very early the next Monday morning, back in those days.

Let me tell you a story. Sometime in the early 2000s, a senior and much older colleague of Abati, perhaps out of malice or envy or both, sought to bruise Abati’s ego at the workplace. The story is told that on that fateful day, to the hearing of not a few people gathered, the big Oga said rather condescendingly: “Everywhere I go, everyone keeps asking me ‘Where is Reuben Abati?! Where is Reuben Abati?!’ They don’t know that, here at The Guardian, you’re nobody!”

Of course, that was a lie. In the estimation of the average reader or follower of The Guardian back then, Abati certainly counted much more. After the exit of titans like Dr. Yemi Ogunbiyi and Dr. Tunji Dare, not a few media scholars would agree that Dr. Reuben Abati came to embody The Guardian in the civic space on account of his high productivity, depth and influence.

To put things in historical context, it must be recognized that, before Nigeria’s independence in 1960, newspaper columnists played a significant role in anti-colonial agitation by way of mobilizing local resistance and they all seemed united for a common purpose back then. However, that unity of pursuit unfortunately devolved into something else in post-colonial Nigeria. As the socio-political dynamics changed with the intensification of power struggle among competing factions of the elite, so did the character of newspaper columns in Nigeria. And part of the consequence is the emergence and proliferation of media organizations which, in some cases, openly aided and abetted the peddling of ethnic or sectional agenda. Nowadays, quite unlike the pre-Independence Nigeria, we see a growing number of columnists in the public space who would rather be identified more as the defender of ethnic, sectional or sectarian interests.

Abati stands as the very antithesis of this parochial tendency. In philosophy and practice, Abati’s journalism is defined essentially by an unflinching fidelity to intellectual curiosity, logic and reason; certainly he will not be listed among the ethnic irredentists. As can easily be seen through his public engagement in almost four decades through the agency of both written and spoken words, Abati would certainly be counted as a passionate advocate of the concept called Nigeria. Perhaps, his greatest strength as a writer is a unique gift to seek winning an argument with the combined artillery of logic and needling humor without being overly abusive. Of course, overall, Abati’s language, his stylistics, bears a distinctive flavor marked by easy accessibility without losing elegance, steeped in native humor that disarms even the supposed enemies or confuse those being mocked so much that they start thinking they were receiving a compliment instead. His multi-disciplinary academic exposure is certainly uncommon among peers and indisputably unique in Nigeria’s broader civic space.

This distinction is very much in evidence in what is now being presented today as an anthology of some of his essays in the last three decades published as columns in The Guardian and Thisday. Some of them won him virtually all the prestigious media awards available to be won in Nigeria over the years, as well as got him inducted as a fellow of the Nigerian Academy of Letters. This rich harvest of essays are thematically classified into three books namely “How Goodluck Jonathan Became President” running into 285 pages; “A Love Letter & Other Stories” running into 402 pages and “PORTRAITS: People, Politics and Society” spanning 642 pages. The books are published by Caltop Publications based in Nigeria.

Writing in his seminal book entitled “On Heroes, Hero-Worship and the Heroic in History”, Thomas Carlyle reminds us of the power of little stories and little drama. The famous Scottish essayist and historian propounded the theory of the “The Man” which underscores how impactful individuals shape history. What then becomes the history of a nation, according to Carlyle, is an aggregation of the biographies of great men that inhabited the epoch under consideration. So, in a way, it can then be argued that, with its range, depth and consistency, Abati’s weekly columns effectively offers an aperture to view the evolution of Nigeria over the past three decades.

But note: Abati’s chronicle is not entirely value-free. He was not a mere verbatim recorder of events or ideas or a biographer for that matter, engaged in a perfunctory exercise. Rather, his own historiography was undoubtedly shaped by the earlier referenced instinctive bias for logic and commonsense which align with what can normatively be classified as the public interest or the common purpose.

The first book entitled “How Goodluck Jonathan Became President” comprises 31 chapters subdivided into four sections. The first captioned “In The Beginning …” details the political and historical circumstances that gave birth to the administration of President Umar Yar’Adua in which Goodluck Jonathan had fortuitously emerged as the deputy. In Chapter Two with the title “The Jonathan Presidency” (on page 29 precisely), Abati sums up popular opinion about the 2007 presidential polls conducted by the Obasanjo administration thus: “In the end, the 2007 elections were regarded as the worst in Nigerian history. On Election Day, television stations showed images of underage voting, ballot box snatching and gross violation of the people’s right to choose. The international community was alarmed, local observers dismissed the election as a sham.”

Indeed, the months between late 2009 and up to the middle of 2010 were quite unprecedented in Nigeria’s history and obviously unanticipated by the framers of the 1999 Constitution, whereby a constitutional vacuum was exploited by the inner circle of a sitting President bedridden in a foreign land with the exact nature of his ailment hidden, plunging governance at home into a state of suspended animation and turning Aso Rock into a theatre of the absurd. Until the 9th of February 2010 when the Senate contrived the Doctrine of Necessity to proclaim the deputy as acting Presidency. The high drama and treacherous intrigues that preceded the emergence of Goodluck Jonathan first as acting President following the Senate’s intervention and eventually as substantive President on May 5 after the death of Umar Yar’Adua are adequately documented in the eleven-part series under the rubric of The Jonathan Presidency in the Section One of the book.

Again, while the Hajia Turai Yar’Adua-led cabal sought to tighten their grip on power in Abuja in her husband’s curious absence, Abati vividly captures the popular mood across the land then in Chapter Fourteen with the title “Thank You, Dora”. Professor Dora Akunyili, the then Information Minister, had summoned the courage to break the conspiracy of silence by opening up on Yar’Adua. On page 129, the author writes: “Dora Akunyili … is obviously the only man in the Executive Council of the Federation, the others have lost their spine and submitted to the tightly knit conspiracy spun by that body and its faceless accomplices in deceiving Nigerians 74 days on, that President Umaru Yar’Adua is fit. Akunyili thoroughly fed up with all the fibbing and shilly-shallying reportedly submitted a memo to the Executive Council this week asking that the deception must stop and that President Yar’Adua must hand over to the Vice President so the country can move on in his absence.”

But as sympathetic as Abati might sound in his portraiture of Jonathan at the hands of the Aso Rock cabal before Yar’Adua passed on, he nonetheless does not hesitate to whip the same Jonathan over his poor habit soon after assuming full power. In a piece entitled “The Speech Jonathan Shouldn’t Have Made” (Chapter 31, page 254), the writer scolds the new President for a tactless talk at the pre-inauguration lecture with the theme: “A Transformation Agenda for Accelerated National Development” after securing an emphatic victory in the 2011 presidential polls.

After being handed the microphone at the said event, according to Abati, it was a moment some tactfulness or even silence would have been golden. Rather, an overly overexcited Jonathan chose to rhapsodize on the inadequacy of four years for a President or Governor to make a big impact in office, thereby setting off alarm bells in some quarters about possible hidden agenda by someone who had not even been sworn in.

Abati’s take is quite ruthless: “If that speech was written for President Jonathan, the speech writer should be suspended, and never allowed to write a Presidential speech again. He says four years is not enough to make a difference, because the government needs to settle down and stabilize. That certainly cannot apply to him. He cannot ask for the luxury of settling down after spending four years in office as Vice President, Acting President, with the last one year as President. Nigerians don’t want him to settle down; they want results. That is why they voted for him.”

(On a lighter note, maybe that explains why President Goodluck Jonathan is still looking for just any way to return to Aso Rock come 2027, twelve years after leaving the same address.)

Overall, compelling as Abati’s rendition of Jonathan’s journey to power might sound, the job is certainly incomplete. The nation undoubtedly yearns for an extension of his documentation to the four years Abati himself spent as Special Adviser on Media and Publicity to President Goodluck Jonathan, consistent with the tradition already set by his predecessor and successors in that office.

He once whetted public appetite with a jeremiad written shortly after Buhari defeated Jonathan in 2015 with the title “When the Phone stopped ringing”. I searched the first book many times. That piece, which went viral at the time, is omitted in this collection. It could have been added, even as an addendum to the Jonathan odyssey at the Villa. Could the omission be deliberate or an oversight?

Abati surely owes us and future generations a debt to share his insider experience as a key player in the highest office at some point in Nigeria’s history. For instance, my brother and friend, Olusegun Adeniyi, who served President Yar’Adua already documented his experience in a book entitled, “Power, Politics and Death: A Front-row Account of Nigeria Under the Late President Umaru Yar’Adua”. Just as the duo of Femi Adesina and Garba Shehu who served President Buhari as senior media aides have equally published their individual memoirs entitled “Working With Buhari” and “According to the President: Lessons from a Presidential Spokesman’s Experience” respectively.

Now, let us transit to the second book entitled “A Love Letter and Other Stories”. If the first book named “How Goodluck Jonathan Became President” dwells on the serious issues of politics, the second one deals with soft matters, as we can already infer from the title. Here, we see the humorist Abati in full throttle, deploying his exceptional competence in English language to satirize, sermonize or philosophize.

“The seventy-seven essays you find here explore the associated themes of love, family values, fame, fortune, pursuit of happiness, human vanity etc. For ease of consumption and digestion, the author classifies the materials into three parts. Part one is called “Love Notes”, the second is “The Nigerian — Citizen and Anti-Hero” and the third is called “The Legacy of Lysistrata”.

The one you might find most hilarious in this collection is the eponymous “A Love Letter” in Chapter One where Abati resorts to self-deprecating homour. He shares an application for romance he had written as a thirteen-year-old, love-smitten schoolboy to a prospective Juliet, as part of a determination to test the power of a new-found puberty. He happened to have chanced on the said old letter while rummaging his personal library. Hear what a naughty thirteen-year-old Abati, otherwise sent to school by parents to learn, intended to send to one Bose precisely on July 10, 1978:

“My dearest, sweetest, fondest, fantastic, extra-ordinary, paragon of beauty a.k.a Bose. I hope this letter meets you in a fabulous state of metabolism, if so doxology. My principal aim of writing this letter to you is to gravitate your mind towards a matter of global and universal importance, which has been troubling my soul.

“The matter is so important. Even as I am writing, my adrenaline is 100 per cent on the Richter scale, my temperature is rising, the wind vane of my mind is pointing North, South and East at the same time; the mirror in my eyes has only your divine image. Indeed when I sleep, you are the one in my medulla oblongata, and I dream about you. I went out to sea in my dream, and I saw you: surrounded by H20 and you in your majesty rose from the abdomen of the sea like Yemoja, the avatar of beauty. Oh, Lord be with us! We are thy servants.”

To know how that adventure in romance ended, you would have to get a copy to read.

No less funny is Abati’s interrogation of the culture of Valentine Day in the context of material exploitation of the male gender. He extensively x-rays this in two essays entitled “When Love Isn’t Enough” and “A De-VAL-ued Life” in Chapter Two and Chapter Three respectively.

To capture the frenzy that precedes the customary celebration of Valentine Day on February 14, Abati observes in Chapter Two thus: “The romantic propaganda can be really oppressive. In the past few days for example, GSM service providers have insisted that the only ring tone that fits this season is the one that forces you to think of romance, just in case you may have forgotten. I didn’t solicit for the ringtone, but I got it all the same and I have had to listen to it, on other people’s lines, and I guess it doesn’t come free.

“The GSM companies are making money selling Valentine messages. And that is the point: the frenzy over Valentine’s Day is commercial, capitalistic, and it is of course, global.”

To sustain the salient points raised in Chapter Two, a very creative Abati resorts to the dialogue technique which helps to incorporate the nuances not easily captured by the prosaic form. Of course, among the tribe of top Nigerian columnists in the last three decades, there can be no dispute that Abati is the master of this technique, which is not surprising considering his doctoral certification in dramaturgy. To draw attention to the deeper concerns, hear the conversation between Abati’s two fictive characters in the next Chapter, that is Chapter Three:

“So, is Venus a Nigerian? I think we Nigerians like to copy white people a lot. Valentine’s Day is all about commerce and illicit sex. Married men running around with small girls, lecherous men sending gifts to other people’s wives, and flirtatious women looking for someone to cuckold them, and everybody pretending to be in love. I say it is a charade. Government should ban it. We can’t afford to have a day when people just fool around, mouthing nonsense.”

Then, the gist partner responded: “I don’t think anybody will agree with you. Government cannot ask people not to love each other. That will be strange.”

However, of the three tomes by Abati under reference, the most definitive, in my mind, is the third one entitled “Portraits: People, Politics and Society”. It reminds of the 690-paged classic by The Times of London entitled “Great Lives — A Century in Obituaries”, edited by Ian Brunskill and published in 2005. Or another by The Economist of London with the title, “Book of Obituaries” edited by Keith Colquhoun and Ann Wroe published in 2008.

But thankfully, Abati’s own is not about only the dead. A good many of the personalities examined in Abati’s third book are still very much alive. Just as “Portraits: People, Politics and Society” showcases the multi-disciplinary virtuosity of Reuben Abati as a compelling presence in Nigeria’s intellectual space for almost four decades, this particular collection will more or less also pass as a roll-call of most — if not all — of the consequential individuals who have shaped and defined Nigeria as well few in the global community in the last four decades.

As usual, for ease of consumption and digestion, Abati subdivides the book into four sections namely “Man-Of-The-Year Essay” (twelve in all published in The Guardian). Then, you have the section tagged “Profiles”, followed by “Different Encounters” and “Birthdays”.

Put together, they are either tributes and mini biographies of a hundred individuals. They cut across politics, commerce, military, academia, journalism, law, science, religion, philanthropy, art and entertainment and even crime. Another title for this collection would be “The saints and the sinners”.

Of course, Abati is not merely documenting them but also passing a value judgment. Those praised will be those who have impacted their society or humanity at large for good. Those lampooned will be those who left or are leaving the country or the world worse than they met it.

Why this third collection by Abati is also significant is for the inspirational appeal in most cases, and as cautionary note in few instances. The young ones should be inspired by the many examples of how small idea started by ordinary folks became big through sheer hard-work, persistence, perseverance and delayed gratification.

This is all the more instructive in a new world we seem to have been thrust in which the wrong heroes are worshipped and wrong values glamorized by the social media. For the impressionable ones who think only Yahoo Yahoo can bring fortune, they will find a rebuke in this collection, for instance, from the story of Jimoh Odutola who started a business with a capital of just Six Pound in 1921 and, thorough a practice rooted in diligence, fear of God and integrity, transformed to a commercial octopus in the next five decades.

A conglomerate that employed thousands in the Southern part of Nigeria. It is no fairy tale. Abati documents his personal relationship with the old man whose disciplined lifestyle ensured he could still visit Abati and climb the stairs at The Rutam House at the Guardian when he was well over 90 years of age. Pa Odutola eventually died at the age of 105 in 2010. Readers will find this in Chapter 27.

And for those who easily get intoxicated by political power, two of Abati’s essays in this collection should serve as a caution. The two are entitled, “Lucy Kibaki’s death: Africa’s Most Violent First Lady” in Chapter 21 and “Ten Years After Lamidi Adedibu” in Chapter 58.

Taken together, the three books are well packaged in a manner that will not only keep the ordinary reader spell-bound, but also earn respect from academic quarters, with not too many typographical infelicities. The indexing presents them as serious academic offerings. Perhaps, the low incidence of typos can be attributed to the fact that all the essays earlier benefited from intense editorial scrutiny before being published in The Guardian and Thisday.

However, I noticed some misalignments in the Table of Contents of the three books. The version I was given for this review was the soft copy. While seeking to reference the chapters, I noticed that the pagination set out in the Table of Contents differs from the actual location in the book. I believe this can easily be remedied, particularly for the copies to be sold in the digital space.

All said, the three books are undoubtedly monumental fittingly reflecting the putative monumentality of Dr Reuben Adeleye Abati, a consequential public intellectual, a media icon, a politician and, more importantly, someone relentlessly advocating for a better Nigeria. Together, these books not only tell the worst and best of us as a nation, but also prognosticate the greatness that awaits us as a nation if only the critical mass can coalesce in the pursuit of a common purpose. I strongly recommend you all get copies to read and pass on to your children, friends and neighbours.

Thanks for your attention.